By Dominique Grisard. This is a special in our series «10 Gründe, Frauen (wieder) neu zu lesen» in the context of «Schreibweisen, Genres und die Verhältnisse der Geschlechter» von Art of Intervention.

1. (Art) theory as liberatory practice

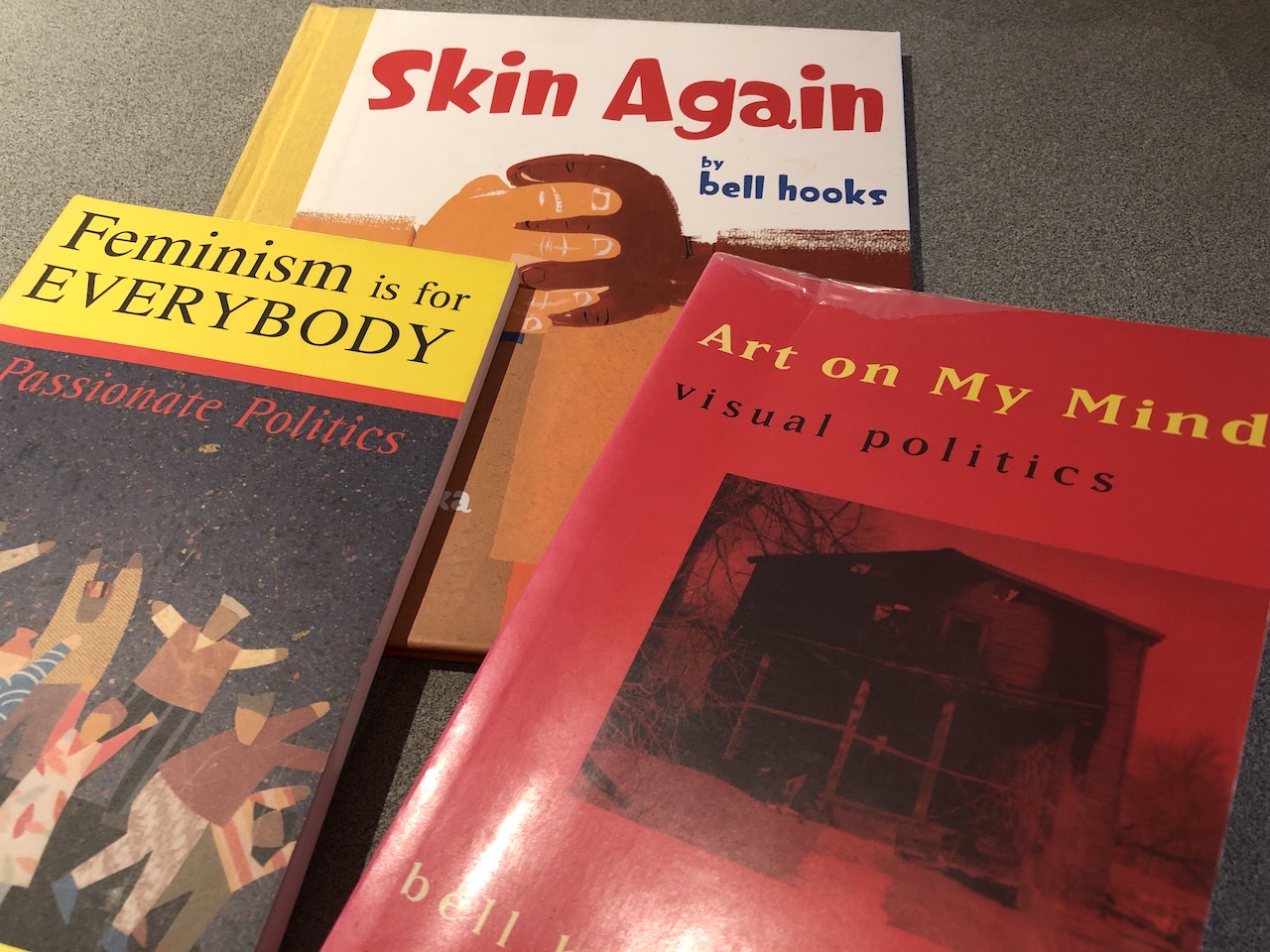

«Art on My Mind» is what this blog is all about. It is also the title of a book (1995) by bell hooks. bell hooks passed away last week. There’s been an outpouring of love for her ever since. She expressed how many of us felt about (art) theory:

I came to theory because I was hurting – the pain within me was so intense that I could not go on living. I came to theory desperate, wanting to comprehend-to grasp what was happening around and within me. Most importantly, I wanted to make the hurt go away. I saw in theory then a location for healing»

bell hooks 1994, 59

hooks was an extraordinary public intellectual, her practice both personal and political, objective and affective, aesthetic and embodied, and always collaborative, in dialogue with a wide heterogeneous group of interlocutors; for «Feminism is for Everybody» (2000) this was her philosophy and the title of another book of hers. It is her big picture perspective, coupled with a decidedly down with the people understanding and compassion for how gender, race and art come to matter that prompted me to revisit «Art on My Mind» and share nine more of her insights in her own words:

2. Being an artist is dangerous

Life taught me that being an artist was dangerous. The one grown black person I met who made art lived in a Chicago basement. A distant relative of my father’s, cousin Schuyler was talked about as someone who had wasted his life dreaming about art. He was lonely, sad, and broke. At least that was how folks saw him. […] And there in the dark shadows of his basement world he initiated me into critical thinking about art and culture. Cousin Schuyler talked to me about art in a grown-up way. He said he knew I had the ‹feeling› for art. […] Now when I think about the politics of seeing – how we perceive the visual, how we write and talk about it – I understand that the perspective from which we approach art is overdetermined by location»

hooks 1995, 2; accentuations by Dominique Grisard (DG)

3. Art matters

Recently, at the end of a lecture on art and aesthetics at the Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe, I was asked whether I thought art mattered, if it really made a difference in our lives. From my own experience, I could testify to the transformative power of art. I asked my audience to consider why in so many instances of global imperialist conquest by the West, art has been other appropriated or destroyed. I shared my amazement at all the African art I first saw years ago in the museums and galleries of Paris. It occurred to me then that if one could make a people lose touch with their capacity to create, lose sight of their will and their power to make art, then the work of subjugation, of colonization, is complete. Such work can be undone only by acts of concrete reclamation»

hooks 1995, xv; accentuations by DG

Photo by «Cmongirl», Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

4. Art and a Black feminist politics of the visual are central to subjectivity and decolonization

most black folks do not believe that the presence of art in our lives is essential to our collective well-being. Indeed, with respect to black political life, in black liberation struggles, […] the production of art and the creation of a politics of the visual that would not only affirm artists but also see the development of an aesthetics of viewing as central to claiming subjectivity have been consistently devalued. […] Representation is a crucial location of struggle for any exploited and oppressed people asserting subjectivity and decolonization of the mind. However, we know that, in the segregated world of recent African-American history, for years black folks created and displayed their art in segregated black communities, and this effort was not enough to make an intervention that revolutionized our collective experience of art. Remembering this fact helps us to understand that the question of identifying with art goes beyond the issue of representation»

hooks 1995, 3; accentuations by DG

5. Art has a transformative impact on Black liberation struggles

Art constitutes one of the rare locations where acts of transcendence can take place and have a wide-ranging transformative impact. Indeed, mainstream white art circles are acted upon in radical ways by the work of black artists»

hooks 1995, 9; accentuations by DG

6. Racism and sexism shape accessibility, commodification and critique of work by Black artists

It is part of the contemporary tragedy of racism and white supremacy that white folks often have greater access to the work of black artists and to the critical apparatus that allows for understanding and appreciation of the work. Current commodification of blackness may mean that the white folks who walk through the exhibits of work by such artists as Betye and Alison Saar are able to be more in touch with this work than most black folks. These circumstances will change only as African-Americans and our allies renew the progressive black liberation struggle – reenvisioning black revolution in such a way that we create collective awareness of the radical place that art occupies within the freedom struggle and of the way in which experiencing art can enhance our understanding of what it means to live as free subjects in an unfree world»

hooks 1995, 9; accentuations by DG

7. Artistic freedom is inseparable from concrete struggles for liberation

Writing about Emma Amos‹ work, hooks underscores the artist’s stance against

a cultural politics of exclusion and denial that would separate the practice of artistic freedom from concrete struggles for liberation. One struggle makes the other possible, not just for African-American artists but for any artist»

hooks 1995, 170; accentuations by DG

8. Black feminist art is constitutive of an ethics of reciprocity and mutual engagement

The convergence of possibility that is hinted at in the painting «Malcom X, Morley, Matisse and Me», is an example of how Amos’s work rejects a binary approach to the politics of difference that would have everyone’s identity be fixed, static, and always separate. She replaces this paradigm with one where mixing is celebrated, where the cultural interchanges that disrupt patterns of domination are dismantled so that an ethic of reciprocity and mutual engagement forms the aesthetic grounds where the subject can be constantly changing»

hooks 1995, 170

9. All art is situated in history – there is no «pure imagination»

Interrogating the way in which aesthetic sensibility is shaped by the particularity of artistic vision, as showing how that vision is informed by constraints imposed by a concrete politics of representation that maintains and perpetuates the status quo, Amos disrupts the essentialist assumption that a pure imagination shapes artistic work»

hooks 1995, 163

10. Growing up with art changes who we are

It is likely hooks’ awareness that stories, the way they are told and whether they are heard, are shaped by a politics of racism and sexism, that prompted her to write accessibly and approachably if also with great clarity, poignancy and urgency. In «Art on My Mind» hooks underscores the importance of art in children’s everyday lives:

Without a doubt, if all black children were daily growing up in environments where they learned the importance of art and saw artists that were black, our collective black experience of art would be transformed»

hooks 1995, 3

Indeed, she teamed up with illustrator Chris Raschka in making the highly stereotypical dichotomous worlds of children’s book more complex, nuanced and poetic, one book at a time. In their 2004 children’s book «Skin Again» hooks and Raschka encourage children to open up to each other:

the skin I’m in will always just be a covering. It cannot tell my story. If you want to know who I am you have got to come inside. Be with me inside the me of me, all made up of stories, present, past, future, some true to life and others all fun and fantasy, all the way I imagine me. You can find all about me – coming close and letting go of who you might think I am»

hooks and Raschka invite children (and the adults in their lives) to practice a politics of mutual engagement with the manifold, at times overlapping and contradictory stories shared.

Literature

bell hooks: Art on My Mind. Visual Politics, New York: The New Press, 1995.

bell hooks: «Theory as Liberatory Practice», in: Teaching to Transgress. Education as the Practice of Freedom, New York/London: Routledge, 1994.

bell hooks: Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, Boston: South End Press, 2000.

bell hooks, illustrated by Chris Raschka: Skin Again. Los Angeles/New York: Disney Jump at the Sun, 2004.

Dominique Grisard ist Historikerin und Geschlechterforscherin am Zentrum Gender Studies der Uni Basel und leitet das Swiss Center for Social Research. Mit Andrea Zimmermann hat sie die Forschungs-, Lehr- und Veranstaltungsplattform The Art of Intervention ins Leben gerufen. bell hooks hat ihr Verständnis von Kunst, Populärkultur und Intervention nachhaltig geprägt.

«10 Gründe, Frauen (wieder) neu zu lesen»

Warum werden runde Geburtstage von Frauen so oft vergessen? Und warum werden diese Jubiläen, wenn überhaupt im bescheidenen Rahmen begangen, von der Öffentlichkeit kaum bemerkt?

Wie kommt es, dass Schriftstellerinnen vergessen werden? Dass ihre Bücher nicht mehr in den Buchhandlungen aufliegen? Dass ihre Stimmen aus dem Feuilleton verschwinden?

Es ist nicht wahr, dass es früher keine schreibenden Frauen gab, und es waren auch nicht wenige, wie die feministische Literaturwissenschaft seit Jahrzehnten zu zeigen nicht müde wird. Aber wie lässt sich der Zirkel des Vergessens und «Wiederfindens» durchbrechen?

Bis heute werden Bücher von Frauen seltener und deutlich kürzer besprochen, erhalten Frauen weniger Vorschuss für die nächste Neuerscheinung als Männer. Und das, obwohl die gesamte Kette des Literaturbetriebs von der Verlegerin über die Buchhändlerin bis hin zur Leserin vorwiegend weiblich ist.

Diese Mechanismen entbehren jeglicher Logik. Und sie zu durchbrechen, kostet viel Mühe und Arbeit – auch viel unbezahlte Arbeit, die zumeist von Frauen geleistet wird.

Mit der Reihe «10 Gründe, Frauen (wieder) neu zu lesen» wollen wir uns auf diesem Blog an Autorinnen erinnern, sie bekannt machen und Bewusstsein schaffen für Geschlechter-ungleichheiten im Literaturbetrieb. Dafür haben wir verschiedene Autor*innen, Akademiker*innen und Künstler*innen eingeladen, über eine Autorin zu schreiben, die ihnen viel bedeutet. Kennst auch DU eine Autorin, die dir viel bedeutet und an die du gerne erinnern möchtest? Hier findest du eine Anleitung (PDF). Bei Fragen schreib uns hier: info@theartofintervention.blog

Photo: bell hooks in 2009, photographed by «Cmongirl» (detail). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.