By Sascia Bailer. A Review of «Curating Difference – Different Curating?» by Art of Intervention at Kunstmuseum Basel.

As curatorial practice finds its etymological origin in the Latin noun cura («care», «attention», or «concern»), it is confronted with an immanent tension between careful representation of marginalized subjectivities, protective attention towards artworks and art workers, affective care for audiences and collaborators, and burdensome responsibility for complex processes, making curating an ambiguous profession. I argue that we as (feminist) curators – who are cognizant of our profession’s etymological root in care – must articulate, in thought and practice, how we can responsibly attend to matters of care from our respective positions of power.

The event «Curating Difference – Different Curating?» by Art of Intervention (organized by Dominique Grisard and Andrea Zimmermann), which took place on December 4th 2023 at Kunstmuseum Basel, can be understood as such an invitation to collectively challenge and renegotiate the agency and the limitations of curating as a care-taking practice. While, over the recent years, we have witnessed an upsurge in exhibitions and public programming in academia and the arts that address questions of care, interdependence, inclusion, and collectivity on a thematic level, we need to shift our attention to the often uncaring, invisibilized structural conditions in the arts.

The first part of the event was titled «Research Lab» and engaged with the structural conditions and possible pathways to transformations in an intimate setup. This part was by-invitation-only and had brought together 29 women from the arts and academia who are active in the Swiss and German landscape. After two lectures by the hosting scholars Dominique Grisard and Andrea Zimmermann on the uneasy relationship between gender, care, and curating, the group was invited to form small groups to discuss different thematic foci, ranging from «leadership», «curating and care», «networking» to «recognizing difference». The central question that the individual groups were asked to respond to was, «What are the tools we need to intervene and transform art institutions from the inside – on a personal and structural level?»

The bringing together of the different group conversations showed just how entrenched the different scales of the individual and the structural are with one another. The conversation, on several occasions, returned to the notion of micro-politics as a field of agency, framing the everyday life as the terrain for social change. One orange sticky note, that had been pinned to the collective board, stated the word «questioning». It seemed as if the agreeable common denominator of the group discussion was, that «questioning» would be the first step to change – a notion that I will return to in the upcoming paragraphs.

The second part of the event was open to the public. It took place in the Vortragssaal in the main building of Kunstmuseum Basel, where around 80 guests joined the «Long Tables» – an artistic format, which had been developed by the feminist artist and activist Lois Weaver in 2004. At Kunstmuseum Basel, the participants were awaited by four long tables that each had a thematic focus: «leadership & power»; «support structures & political alliances»; «curating: challenges & interventions»; «coalitions & networks». On each table, the organizers had placed two to four moderators, of whom many currently hold leading positions within the Swiss arts and research landscape, such as Elena Filipovic (Director Kunsthalle Basel, des. Director Kunstmuseum Basel), Kabelo Malatsie (Director Kunsthalle Bern) or Katrin Grögel (Head of Department of Culture, Basel-Stadt).

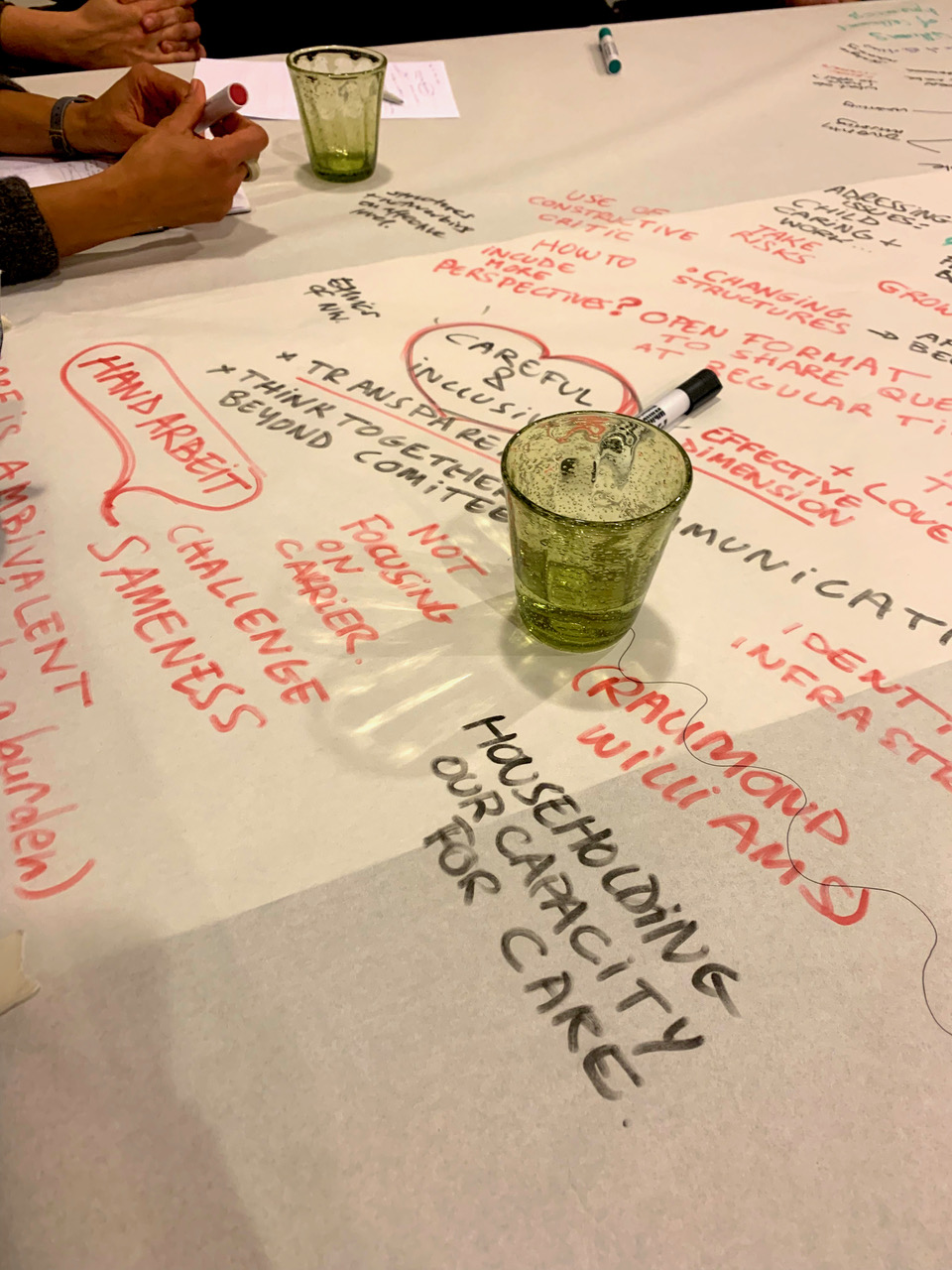

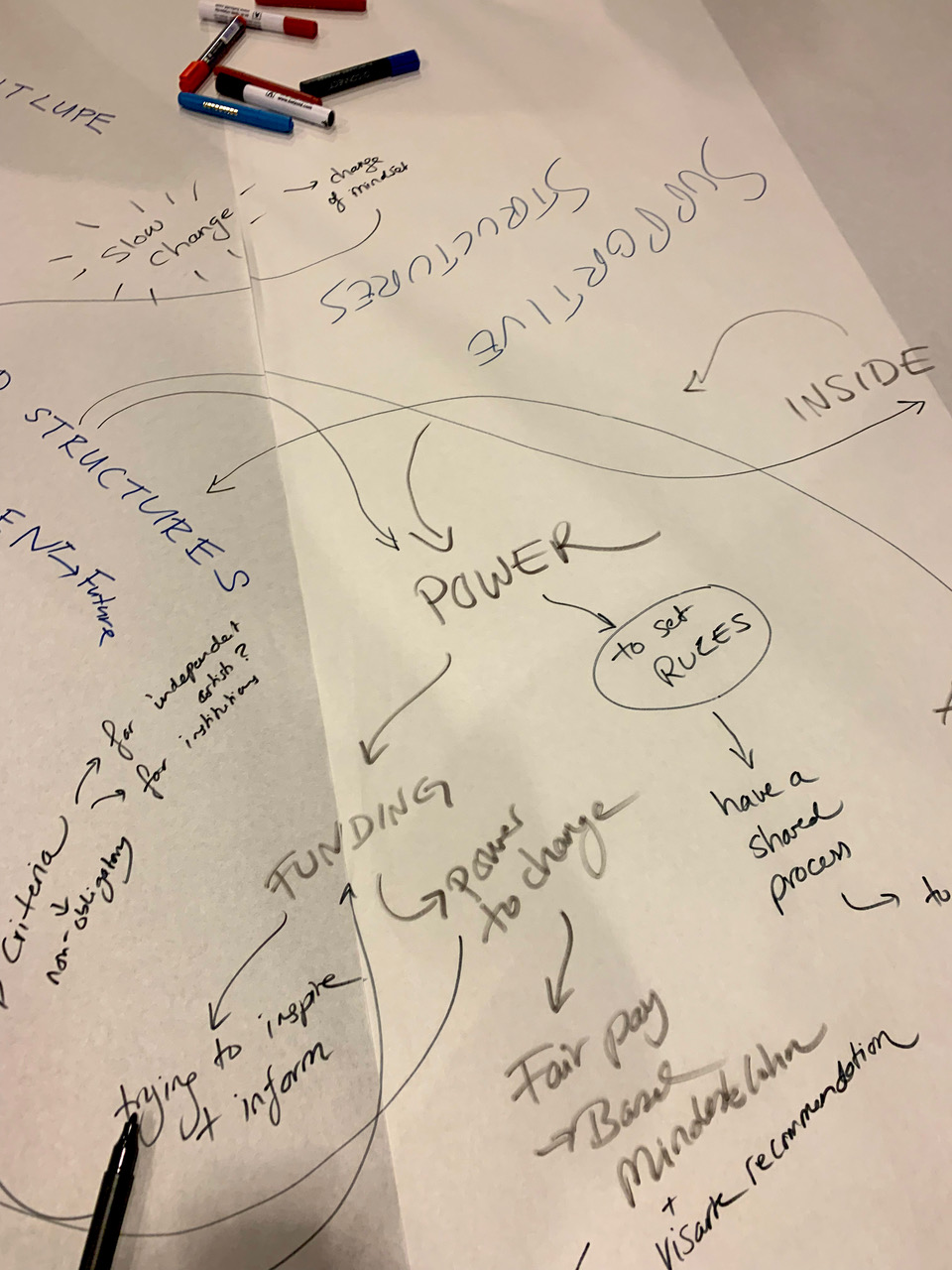

The audience joined the moderators on their tables, extra chairs were squeezed in to account for the many visitors. Each session was kick-started by short statements of the moderators, which were then followed by questions and remarks by the other participants. Everyone was invited to use the array of pens to write and sketch on the large paper rolls that were spanning the tables. At the end of each 20 min. session (there were three rounds in total), we would switch from one thematic table to the next. The room was buzzing with voices and chatter, the air was stuffy, but the conversations were as engaged and lively as one could hope for.

Yet, due to the temporal limitations, pressing questions and not so many solutions dominated the evening. In order to return to the notion that «questioning» may form the first micropolitical act towards transformation, I want to make transparent a selection of pending questions that linger on – both as a way to invite the reader of this text to join this transformative quest, but also as a reminder of the work that still lies ahead of us:

How can we lead in a different – caring – way without being perceived and called out as «unprofessional»? Are the feminist principles of eradicating hierarchies, as forms of oppression, reconcilable with leadership at all? If it is about acknowledging the existing power structures, how can we use them for the greater good? Power in the arts is considered an «ugly word» – is that why we rarely address it in a productive manner? If invisible power exists, how can we deal with it? Can power also be considered a «burden of responsibility»? And is this in direct contrast with arts‘ vision of being free? Could we begin to use power as a verb? What would institutions look like if they were to follow democratic or even consensus-seeking techniques of decision-making? How can institutions become more caring? If so, for whom or for what – their audiences, artworks, colleagues, employees or community members? What happens when someone comes in and changes all the unwritten rules? Can transparency be a vehicle for change, or does it only lay inequalities bare without transformative consequence? What if we were to curate in such a way as if the world was already in a good place, as if the world were already equal, as if the world were without racism? How do we build and maintain networks if our caring resources are already limited or exhausted? How can the recognition of the limited resources that we have for caring for ourselves and others be institutionalized? How can we practice these vulnerabilities, that we speak of, when we engage with institutions? How do we speak up as critical voices without putting ourselves at risk? How can we fight the precarity of the arts by collectivizing? How can we put pressure to hold (funding) institutions accountable? What is the role of funding in relation to structural changes within the arts? How much structural change can a funding body truly spark? How can care become present in the arts not only as a buzzword but as a practice, a working method that transforms the (infra)structures of the artistic field?

While the raised questions speak to the participants’ criticality and the willingness to transform the status quo of the arts, the event itself was not a utopian place that operated outside of existing mechanisms of hierarchies and cultural precarity: The invited moderators were predominantly people with respected institutional jobs; the voices of independent practitioners came through in the participants’ voices, but the public visibility was granted to names that already held positions of power. On the long tables, time for discussion was limited, and not everyone was able to speak or share their positions – allocating speaking time along the lines of predefined roles (moderators vs. audience) or along characters, to the disfavor of more timid voices. The upbeat atmosphere of a “happening” sparked lively conversations but also seemed to exhaust some of the moderators and participants, who might have needed a more contained and intimate space for conversation.

Further, the grant, which funded the event, did not allow for the coverage of honoraria, which can be regarded as an example of how the invisible (infra)structures of the arts pre-define in which ways curatorial (financial) care can be allocated – for most of the invited moderators and experts this meant that their participation had to be seen as a work commitment within the frameworks of their employment, for freelancers alternative forms of compensation had to be negotiated in lieu of a speakers fee. This example brings to the fore the necessity to not only address and transform the visible spheres of art sector but to shed light onto the fields that are often lacking transparency: those of funding and budgets. In the cultural sector, there is a pressing necessity to synchronize the thematic foci of our cultural events and exhibitions with the underlying, often invisible structures that support the public programming, to make transparent the unequal modus operandi of the arts, and to collectively strive for an otherwise.

As a feminist researcher and curator who works on care, I argue that the caring turn within the arts and academia cannot be counted as a celebratory moment until the representational engagements with care are thought and practised in tandem with concrete manifestations of feminist care within the (infra)structures of the arts.[1] Hence, the political momentum of such events lies not only in gathering these critical voices but in the ability to sustain them long-term – to transform fleeting moments into movements that alter not only what becomes public, but also the conditions of what lies beneath, hidden: the (infra-)structures of the arts.

In light of the contradictions of curating, care, and the capitalist framework, curating with care as a feminist and queer vision may have to be regarded as a project, to speak in Sara Ahmed’s words, who argues that feminism, and the negotiation of the relationship between women is, indeed, a project – «because we are not there yet».[2] This notion of the not-there-yet is also found in the writings of queer cultural theorist José Esteban Muñoz, who articulated that «queerness is always in the horizon» as a way to inspire imaginations towards queer futurity.[3] Following these two scholars, I argue that a curatorial practice that truly enacts care in all its facets, remains visible on the horizon, even if we have not arrived yet. It is the glimpses of its vision that are the driving motor of the quest for an art sector that not only speaks about care but that actualizes it through its (infra)structures.[4] Let us embark.

[1]. Sascia Bailer. Caring Infrastructures. Transforming the Arts Through Feminist Curating With Care. Unpublished Manuscript. Zurich University of the Arts & University of Reading, 2024.

[2]. Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017, p. 14.

[3]. José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: NYU Press, 2009, p. 11.

[4]. Sascia Bailer, see footnote 1.

Image: Long Table discussions at Kunstmuseum Basel, moderated by Dominique Grisard. Image: Sascia Bailer.