This discussion by Lesley Braun is based on a lecture given by Michèle Magema in 2018 in the context of the lecture series, The Art of Intervention, in collaboration with the War Games exhibition at Kunstmuseum Basel | Gegenwart.

Heads of Power

The Democratic Republic of Congo’s fraught history of imperial domination, colonial rule, and political dictatorship, continues to haunt this vast, richly mineral laden land. In 2019, Joseph Kabila, the country’s president of nearly twenty years, reluctantly agreed to cede power in and hold presidential elections. Indeed, African strongmen are no exception in the contemporary world of politics. Perhaps the most notorious strongman to have ruled the Congo for the longest is Mobutu Sese Seko. Among some of his more ambiguous legacies, he introduced a series of cultural and political policies intended to revalorize the country’s pre-colonial history and instill a new sense of African identity to perform nationally as well as on the world stage. One of these policies, implemented in the 1970s when the country was renamed Zaire, and inspired by Léopold’s Senghor’s négritude philosophy, was called authenticité. Within authenticité, a program designated as animation culturelle et politique showcased what Mobutu saw as the country’s most valuable resource: dance performance.

Photo courtesy of M. Magema.

Mobutu’s revalorization of cultural traditions was perhaps most directly reflected in an official speech in which he declared,

“It is when a people can communicate and say what is felt in his heart through song and dance that he is happy”.

The deployment of the masculine pronoun here perhaps obscures women’s presence, especially since women were visible political players during this era, particularly in the realm of dance performance. It is the dynamic between visibility and invisibility that structures much of Michèle Magema’s artistic practice.

Born in Zaire in 1977, at the height of the authenticity campaign, Michèle Magema vividly remembers the evenings gathered around the television, watching the national nightly program featuring Mobutu’s head descending from the clouds—a visual signal that marked the beginning of the mesmerizing animation politique televised dance performances. Her multimedia body of work reflects not only the machinations of state-level patriarchal power, but also women’s positions within, and outside it. The fragmented images of women, their disjointed moving parts creating new formations themselves, are potent reminders of the country she left behind. Magema often places women at the center of her oeuvres, a counterpoint to the heavily male-dominated work created in and about the Congo.

While she does not shy away from engaging with the notion of global feminisms—in 2007, Magema shared a selection of her work at the Brooklyn Museum of Art’s show Global Feminisms —she also challenges the impulse to universalize women’s experiences. In addition to museum exhibitions around the world, including at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) and the Rietberg Museum in Zurich, her work has been featured at both the Lubumbashi and Dakar Biennials. She most recently had a solo show at the Kunsthal Extra City in Belgium entitled Watermarks, Silent traces.

In November of 2018, Michèle Magema gave a dynamic, multimedia lecture entitled Performing in public space at the time of identity claims and political resistances, at the Kunstmuseum Basel Gegenwart as part of The Art of Intervention series. The talk was constructed around her personal biography, narrating her body of work as well as her relationship to Zaire, a country that no longer exists in name. Magema sees her life course as inextricably linked to her artistic production.

Instead of communicating feelings of errancy, Magema engages with her emotional landscapes by superimposing experiences of nationalism culled across her personal history. Settling in Paris in the early 1980s, the Magema family left their home country when it was still called Zaire. Looming in their new city’s social imaginary is Marianne, the symbol of the Republic, standing in opposition to monarchy. Posed as Delacroix’s iconic image of Marianne with the tricolored flag, Magema intrudes the image with one arm outstretched while the other brandishes a gun, signaling sovereignty primarily through the use of flags. Both movement and motion motivate this photograph: while the movement of the arm indicates the abrupt actuality of political revolution, the motion of the flags reference their iconic imagery/function of claiming sovereignty over a territory.

Right: Eugène Delacroix, La Liberté guidant le peuple, 1830 (Ausschnitt). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

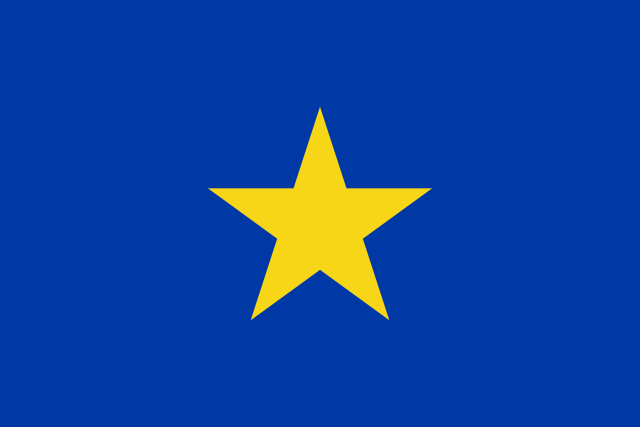

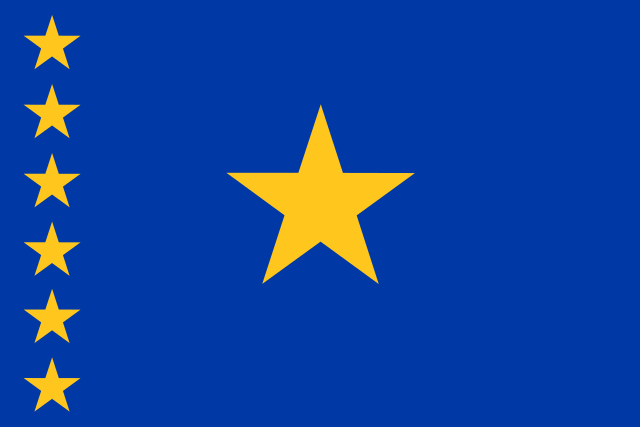

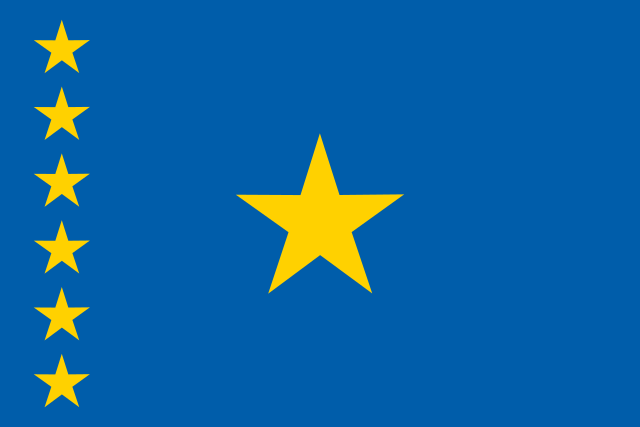

Nationalist symbols are further echoed in her later performances, in which color associated with flag is incorporated in the service of reflecting upon and creating African national narratives of independence. To date, there have been eight official flags associated with the region currently known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, each one becoming its own archive. The repeating forms, particularly the dominant star, anchor the design, and evoke a nostalgic return. Indeed, the Zairian flag starkly stands out as a punctuated singular expression within the design sequence, a visual break from the circling continuity of the past and present color configurations.

A visual represenation of the regions historical flags. Source: Wikipedia.

The Feminine in Motion

One of her most famous pieces, Oyé Oyé (2002), which won the Prix du President de la République Senegalaise at the 2004 Dakar Biennial, references a popular slogan uttered at the time of Congo’s independence. The two channel-video installation features a marching woman (the artist herself) donning a dress inspired by her primary school uniform, while the second screen presents viewers with a montage of historic images of dancing animatrices politiques, and crowds of onlookers. Magema’s confident, rhythmic strides, punctuated by swinging arms, appear in between the archival footage, at different speeds, propelling her forward. The marching woman’s head is cropped out of the picture, leaving viewers to gaze at the woman’s body in motion, gesturing towards the larger interplay between invisibility and visibility. Mobutu, donning his signature leopard hat, is present in the video along with rows of parading young girls and women clad in raffia skirts performing African ballet in a stadium setting. Viewers must shift their attention continuously between the two screens—the disjuncture suggestive of the kaleidoscopic relationship within and across the mass and spectators.

Oyé Oyé video (2002), running simultaneously on side-by-side monitors.

Photos courtesy of M. Magema.

The headless woman sporting a sash across her school uniform, is evocative of both the country’s flag, as well as of beauty pageants, or “miss” contests, which are a potent symbol of femininity in Congo and elsewhere. The loosely edited montage produces a disquieting effect: The sequences of bodies in motion, paired with anachronistic images, almost disorient, and it is within this blurred space that Magema offers a rumination on ritual displays of power.

Balancing Wounded Time

Marcel Mauss’ Techniques of the Body (1973 [1935]) describes the ways in which bodily activities, such as walking, marching, balancing, and dancing are culturally learned and inscribed in the body. At the heart of much of Magema’s work is Mauss’ supposition that the body is our most “natural tool”. In Magema’s words,

“The use of my own body is inspired by the complexities of the woman, and how these are expressed.»

This is why, according to Magema, the body forms part of her practice and is central in her performances. For her, performance is the most direct way of self-expressing, particularly since she understands her body to be a site in which memory is stored. During artist talks, she often references how the Bakongo ethnic group, which Magema’s family descends from, conceptualizes the human as consisting of: the body (Kikingo: nintou); the blood (menga); the soul (moyo).

Delving into her own embodied archive, Magema’s videos demonstrate some of the techniques that form part of her muscle memory, which she describes as “balancing” in the physical and symbolic sense: In Elément, a video piece from 2005, she appears in white high heels, balancing a bucket atop her head. Magema chooses to set her female body in motion to resist the structural forces that govern her.

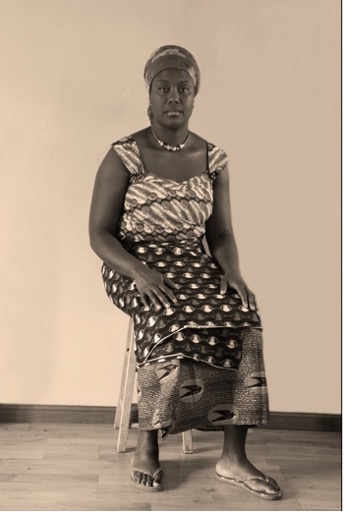

Michèle Magema Mémoire Hévéa (2016), Photo triptych. Photos courtesy of M. Magema.

The photographic series Mémoire Hévéa, on permanent display at the Belgian Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, features a triptych of portraits of the artist’s grandmother at the head of her family lineage. She pays homage to her great grandmother and grandmother and renders visible the polyphonic presence of women then and now. Their invisible legacies, she moves forward in her art. In an interview I carried out with Magema, she offered a meditation on the significance of movement and motion:

“Movement implies a change in position of an object in relation to a fixed point in space, while motion constitutes a change of location or position of an object with respect to time.”

Interview (2017) in Nevers, France

Magema plays with these kinetic concepts as she navigates her different identities through time and space. Her engagement with visualizing circulating forms of postcolonial power structures yields new questions about the position of women in a country where bodies read as female continue to be contested by various stakeholders. Like the women in motion featured in Oyé Oyé—the marching and dancing bodies—Magema shows us women’s movement and motion through various matrices of authoritarian power in Congo and beyond.

Lesley Braun is Senior Lecturer at the Institute for Social Anthropology at University of Basel. Thematically, her research investigates the gendered dimensions of transnational mobility, and how gender and sexuality impact, as well as shape women’s activities in the public sphere. She is also interested in artistic practices in Kinshasa, DRC, and the ways that popular dance – in its embodied and symbolic forms – participates in the construction of an urban experience.

Image: The Triptych, 2011. Installation with three photos, 20×660 cm (detail). Photo courtesy of M. Magema.